This document describes cell 0.0. For development docs, go here.

User Guide¶

“We are all merely Actors” Ask Solem

Basics¶

Quick Cheat Sheet for Agents

a.spawn(cls, kwarg=value)start a remote actor instancea.select(cls)returns a remote actor instance if actor of type cls is already starteda.kill(id)stops an actor by id

Quick Cheat Sheet for Actors

a.send.method(kwarg=value, nowait=False)invoke method on the remote actor instance asynchronously returns AsyncResulta.send.method(kwarg=value, nowait=False)invoke method on a remote actor instance synchronouslya.throw.method(kwarg=value)invoke method on a remote actor of type a instance asynchronouslya.scatter.method(kwarg=value)invoke method on all remote actors of type a

Create an Actor¶

To implement a new actor extend Actor class.

Actor behaviour (all supported methods) should be implemented in the internal

state class.

class Logger(Actor):

class state(Actor.state):

def log(self. msg):

print msg

Then the actor can be started (spawned) remotely using cell.agents.dAgent.spawn()

from kombu import Connection

from cell.agents import dAgent

agent = dAgent.Connection()

logger_ref = agent.spawn(Logger)

Actors and ActorProxy¶

We do not create instances of actors directly, instead we ask an dAgent

to spawn (instantiate) an Actor of given type on a remote celery worker.

logger_ref = agent.spawn(Logger)

The returned object (logger_ref) is not of Logger type like our actor, it is not even an Actor.

It is an instance of ActorProxy, which is a wrapper (proxy) around an actor:

The actual actor can be deployed on a different machine on different celery worker.

ActorProxy transparently and invisibly to the client sends messages over the wire to the correct worker(s).

It wraps all method defined in the Actor.state internal class.

Select an existing actor¶

If you know that an actor of the type you need is already spawned, but you don’t know its id, you can get a proxy for it as follows:

from examples.logger import Logger

try:

logger = agent.select(Logger)

except KeyError:

logger = agent.spawn(Logger)

In the above example we check if an actor is already spawned in any of the workers.

If Logger is found in any of the workers, the agents.Agent.select() will throw

an exception of type KeyError.

Actor Delivery Types¶

Here we create two actors to use throughout the section.

logger1 = agent.spawn(Logger)

logger2 = agent.spawn(Logger)

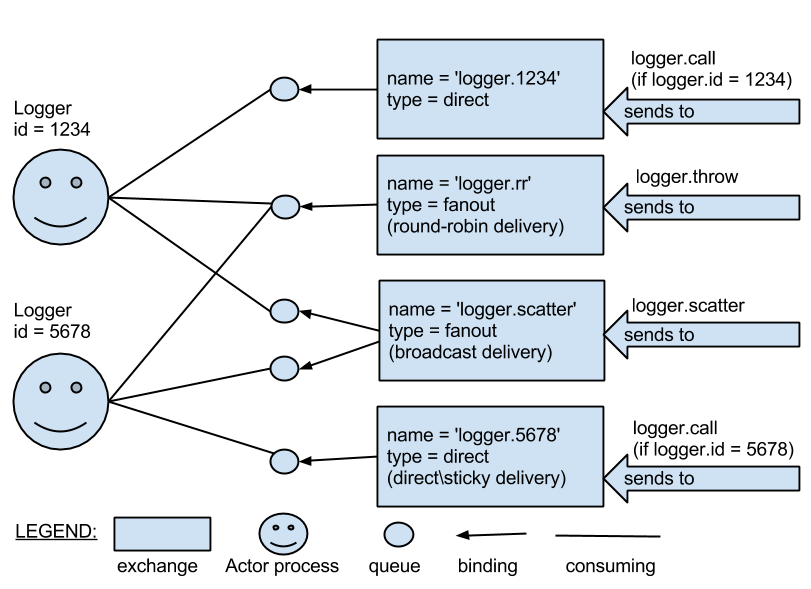

logger1 and logger2 are ActorProxies for the actors started remotely as a result of the spawn command. The actors are of the same type (Logger), but have different identifiers.

Cell supports few sending primitives, implementing the different delivery policies:

- direct (using

send()) - sends a message to a concrete actor (to the invoker)

logger1.send('log', {'msg':'the quick brown fox ...'})

The message is delivered to the remote counterpart of logger1.

- round-robin (using

throw()) - sends a message to an arbitrary actor with the same actor type as the invoker

logger1.throw('log', {'msg':'the quick brown fox ...'})

The message is delivered to the remote counterparts of either logger1, or logger2.

- broadcast (using

scatter()) - sends a message to all running actors, having the same actor type as the invoker

logger1.scatter('log', {'msg':'the quick brown fox ...'})

The message is delivered to both logger 1 and logger 2. All running actors, having a type Logger will receive and process the message.

The picture below sketches the three delivery options for actors. It shows what each primitive does and how each delivery option is implemented in terms of transport entities (exchanges and queues). Each primitive (depending on its type and the type of the actor) has an exchange and a routing key to use when sending.

Emit method or how to bind actors together¶

In addition to the inboxes (all exchanges, explained in the Actor Delivery Types), each actor also have an outbox. Outboxes are used when we want to bind actors together. An example is forwarding messages from one actor to another. This means that the original sender address/reference is maintained even though the message is going through a ‘mediator’. This can be useful when writing actors that work as routers, load-balancers, replicators etc. They are also useful for returning result back to the caller.

How it works?

The emit() method explicitly send a message to its actor outbox.

By default, no one is listening to the actor outbox.

The binding can be added and removed dynamically when needed by the application.

(See add_binding() and remove_binding() for more information)

The |forward| operator is a handy wrapper around the add_binding() method.

Fir example The code below binds the outbox of logger1 to the inbox of logger2

(logger1 |forward| logger 2)

Thus, all messages that are send to logger1 (via emit()) will be

received by logger 2.

logger1 = agent.spawn(Logger)

logger2 = agent.spawn(Logger)

logger1 |forward| logger2

logger1.emit('log', {'msg':'I will be printed from logger2'})

logger1 |stop_forward| logger2

logger1.emit('log', {'msg':'I will be printed from logger1'})

Type your method calls¶

Passing actor methods as a string is often not a convenient option.

That’s why we provide an API to call the method directly. The ActorProxy class returns a partial when any of the Actor API methods is called (call, send, throw, scatter)

actor.api_method.state_method_to_be_called returns a partial application of actor.api_method with firtsh argument set to method_to_be_called.

Therefore, the following pair of executions on the instance of :py:class: ActorProxy are teh same

Note that if the state_method_to_be_called does not exist in the :py:class: ActorProxy.state an exception ( AttributeError()) will be thrown.

logger.send.log({'msg':'Hello'}, nowait=False)

logger.send('log', {'msg':'Hello'}, nowait=False)

logger.call.log({'msg':'Hello'}, nowait=False)

logger.call('log', {'msg':'Hello'}, nowait=False)

logger.throw.log({'msg':'Hello'}, nowait=False)

logger.throw('log', {'msg':'Hello'}, nowait=False)

logger.scatter.log({'msg':'Hello'}, nowait=False)

logger.scatter('log', {'msg':'Hello'}, nowait=False)

# throws `AttributeError` on the sender

# and the message is not sent

logger.scatter.my_log({'msg':'Hello'}

Getting the result back¶

Cell supports several types of return patterns:

- fire and forget - whenever the nowait parameter is set to True, apply to all

cell.actors.Actor()) methods - returning future - apply only to

cell.Actors.call(). It returnscell.Actors.AsyncResultsinstance when invoked with nowait is False. The result can be accessed when needed viacell.Actors.AsyncResults.result(). - blocking call (returning the result) - apply to

cell.Actors.send()andcell.Actors.throw()when invoked with nowait = False - generator - apply to

cell.Actors.scatter()when invoked with nowait = False

ScatterGatherFirstCompletedActor¶

Here is how you can send a broadcast message to all actors of a given type and wait for the first message that is received.

from cell.agents import first_reply

first_reply(actor.scatter('greet', limit=1)

You can implement you own first_reply() function. Remember that the scatter method returns generator.

Then all you need to do is call its next() method only once:

def first_reply(replies, key):

try:

return replies.next()

except StopIteration:

raise KeyError(key)

Collect all replies¶

if limit is not specifies, the

# returns a generator

res = actor.scatter('greet', timeout = 5)

# Iterate over all the results until a timeout is reached

for i in res:

print i

Request-reply pattern¶

Note

When using actors, always start celery with greenlet support enabled!

(see `Greenlets in celery`_ for more information)

Depending on your environment and requirements, you can start green workers in one of these ways:

When greenlet is enbaled, each method is executed in its own greenlet.

Actor model prescribes that an actor should not block and wait for the result of another actor. Therefore, the result should always be passed via callback. However, if you are not a fen of the CPS (continuation passing style) and want to preserve your control flow, you can use greenlets.

Below, the two options (callbacks and greenlets) are explained in more details:

- via greenlets

Warning

To use this option, GREENLETS SHOULD BE ENABLED IN THE CELERY WORKERS running the actors. If not, a deadlock is possible.

Below is an example of Counter actor implementation. To count to a given target, the Counter calls the Incrementer inc method in a loop. The Incrementer advance the number by one and returned the incremented value. The loop continues until the final count target is reached.

class Incrementer(Actor):

class state:

def inc(self, n)

return n + 1

def inc(self, n):

self.send('inc', {'n':n}, nowait=False)

class Counter(Actor):

class state:

def count_to(self, target)

incrementer = self.agent.spawn(Incrementer)

next = 0

while target:

print next

next = incrementer.inc(next)

target -= 1

The actors (Counter and Incrementer) can run in the same worker or can run in a different workers and the above code will work in both cases.

What will happen if celery workers are not greenlet enabled?

If the actors are in the same worker and this worker is not started with a greenlet support the Counter worker will be blocked, waiting for the result of the Incrementer, preventing the Incrementer from receiving commands and therefore causing a dealock. If the worker supports greenlets, only the Counter greenlet will block, allowing the worker execution flow to continue.

- via actor outboxes

class Incrementer(Actor):

class state:

def inc(self, i, token=None):

print 'Increasing %s with one' % i

res = i + 1

# Emit sends messages to the actor outbox

# The actor outbox is bound to the Counter inbox

# Thus, the message is send to teh Counter

# and its count message is invoked.

self.actor.emit('count', {'res': res, 'token': token})

return res

def inc(self, n):

self.send('inc', {'n':n}, nowait=False)

class Counter(Actor):

class state:

def __init__(self):

self.targets = {}

self.adder = None

# Here we bind the outbox of Adder to the inbox of Counter.

# All messages emitted to Adder are delegated to the Counter inbox.

def on_agent_ready(self):

ra = Adder(self.actor.connection)

self.adder = self.actor.agent.add_actor(ra)

self.adder |forward| self.actor

def count(self, res, token):

if res < target:

self.adder.throw('add_one', {'i': res, 'token': token})

else:

print 'Done with counting'

def count_to(self, target):

self.adder.throw('add_one', {'i': 0, 'token': token})

def on_agent_ready(self):

self.state.on_agent_ready()

The above example uses the outbox of an actor to send back the result. All operations are asynchronous. Note that as a result of asynchrony, the counting might not be in order. Different measures should be takes to preserve the order. For example, a token can be assigned to each request and used to order the results.

Scheduling Actors in celery¶

- when greenlets are disabled

All messages are handled by the same thread and processed in order of delivery. Thus, it is up to the broker in what order the messages will be delivered and processed. If one actor blocks, the whole thread will be blocked.

- when greenlets are enabled

Each message is processed in a separate greenlet. If one greenlet/actor blocks, the execution is passed to the next greenlet and the (system) thread as a whole is not blocked.

Receiving arbitrary messages¶

An actor message has a name (label) and arguments. Each message name should have a corresponding method in the Actor’s internal state class. Otherwise, an error code is returned as a result of the message call. However, if fire and forget called is used (call with nowait argument set to True), no error code will be returned. You can find the error expecting the worker log or the the worker console.

If you want to implement your own pattern matching on messages and/or want to accept generic method names,

you can override the default_receive() method.

Exceptions¶

It can happen that while a message is being processed by an actor, that some kind of exception is thrown, e.g. a database exception.

What happens to the Message¶

If an exception is thrown while a message is being processed (i.e. taken out of its queue and handed over to the current behavior), then this message will be lost. It is important to understand that it is not put back on the queue. So if you want to retry processing of a message, you need to deal with it yourself by catching the exception and retry your flow.

What happens to the actor¶

Actor is not stopped, either restarted, it can continue receiving other messages.